by David Broockman — Reposted by Efrén O. Pérez, Valerie Mueller, Sylvain Laurens

aprecruit.berkeley.edu/JPF05187

youtube.com/watch?v=Ay4D...

by Anne Applebaum — Reposted by David Broockman, Jesse H. Kroll, Karen R. Lips , and 1 more David Broockman, Jesse H. Kroll, Karen R. Lips, Paul L. Morgan

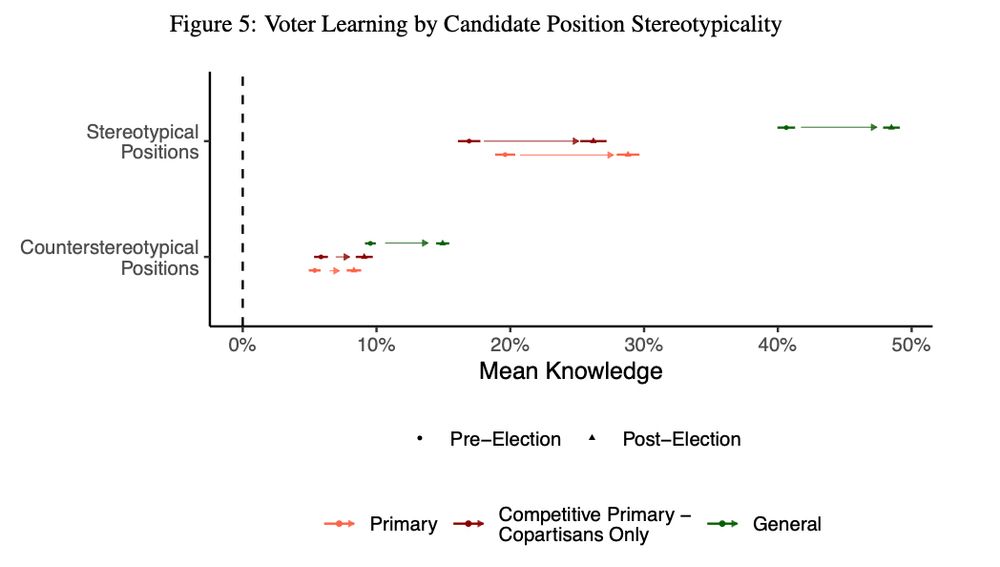

In general elections, party labels give voters huge clues about candidate positions. In primaries, all candidates have the same party label—so these cues are useless for choosing between them.

The opposite of conventional wisdom about incompetent general voters & aware primary voters

In generals, this includes when the closest candidate is an outpartisan–party loyalty isn’t everything.

Both primary AND general election voters change their votes when they learn candidate positions—by a very similar amount…

By election day, general election voters correctly identify 40% of candidate positions vs just 22% for primary voters.

We measure knowledge & learning of 122 candidate issue positions in the 2024 Congressional primaries and 269 candidate issue positions in the 2024 Congressional generals.

• Primary voters who closely follow politics & prefer extremists

• General election voters who are too ignorant of candidate positions—or too “intoxicated” by party loyalty—to vote for moderates over extremists

But our data tells a different story…

For the record, I don't think my work indicates this.

Rather, it suggests that the most advantageous moderation is on the specific issues where a party is out of step with public opinion.

Reposted by David Broockman

aprecruit.berkeley.edu/JPF04782

www.cambridge.org/core/journal...

It’s also a different situation in that LIHTC funds are limited & redistributing them doesn’t have the same issues as, eg, simply not building housing or semiconductor fabs does.