Day job = Associate Prof. of Political Science at UC Berkeley. Tweets = personal views.

Reposted by David Broockman

But our findings suggest that "fear of an ugly America" is an underrated driver of the housing crisis and could contribute to what has been called NIMBYism. Addressing it could unlock new support for more housing.

First, design matters. If the YIMBY movement wants to build broad coalitions, it cannot ignore aesthetics. Policies that ensure better design or "fitting in" (like form-based codes) might reduce political friction.

NB: I used to live in building (b), and it passed SF's design review. Voters hate it and don't want to approve housing like it! Maybe our design review processes should be better.

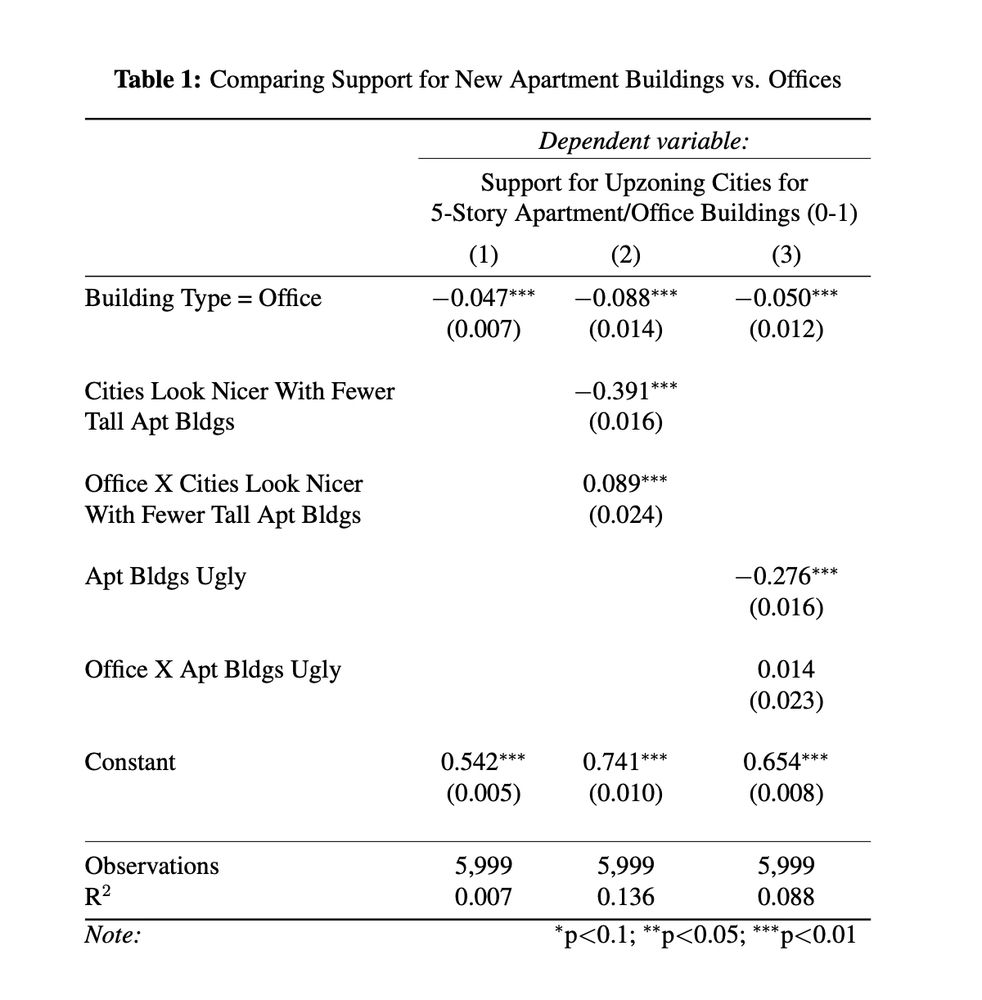

The results also confirm that both visual appeal and fit in context powerfully drive support for housing, and seemingly far more than affordability concerns.

Perhaps part of why single family homeowners oppose local density isn't NIMBYism, but a widely shared view density should go in already-dense areas

Result 1: The aesthetic quality of the project was a massive driver of support--outweighing concerns about parking or tax revenue.

Result 2...

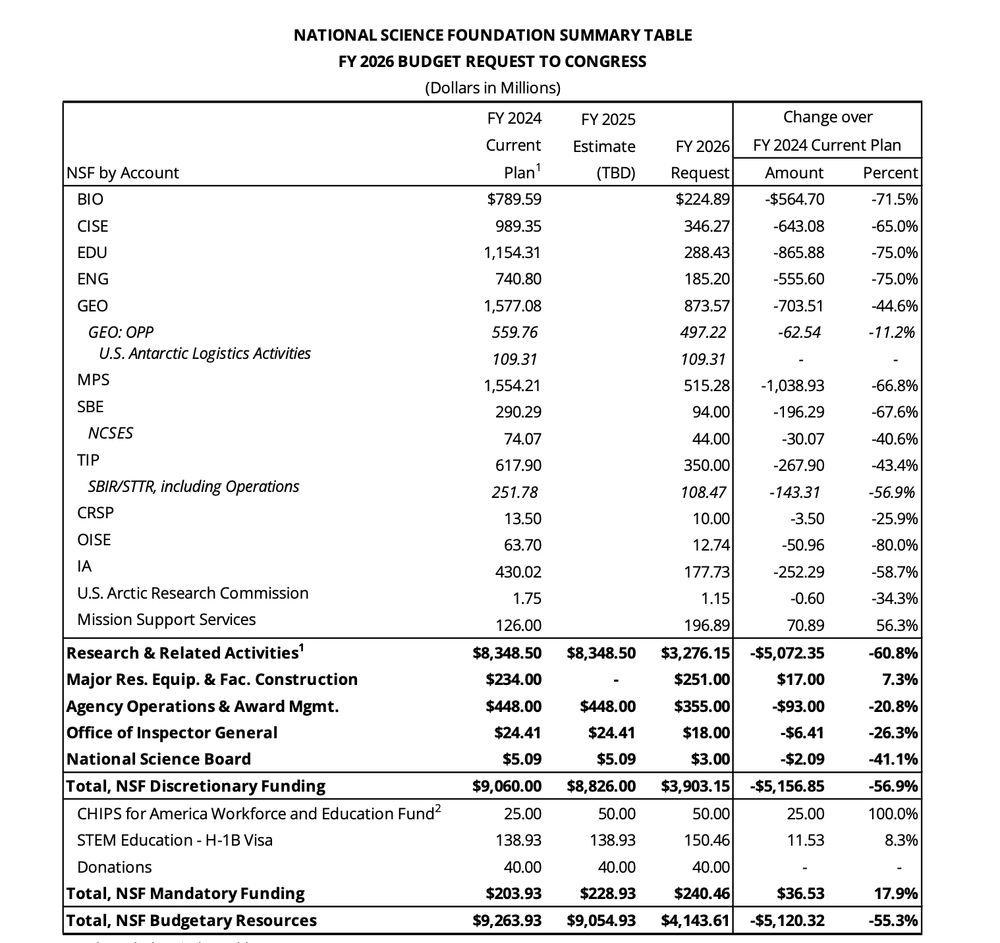

We surveyed voters on various objections to housing. As Figure 3 shows, the belief that "Cities look nicer when they have fewer tall apartment buildings" is a top predictor of opposition.

Even people who live in dense areas support density more where they live than elsewhere!

1. People self-select into neighborhoods that match their aesthetic tastes. If you live in density, you likely have a "taste" for it.

2. Voters prefer development that "fits in" with the existing built environment....

Existing theories predict homeowners in dense areas should be the biggest opponents of more density in already-dense areas--it's their backyard!

But homeowners on corridors are actually *most* supportive of AB 2011-style upzoning of corridors!

Voters form automatic judgments about whether a building is visually appealing or "fits in."

Importantly, they apply these aesthetic standards broadly—not just on their own block, but wherever housing is proposed.

Difference between homeowners & renters often aren't large.

& noting that NIMBYism is real leaves open the question of the content of NIMBY concerns and how they can be mitigated.

"Homevoters": Homeowners protecting property values.

"NIMBYism": Neighbors fearing local nuisances (traffic, parking) in their "backyard."

Reposted by Brendan Nyhan, Scott Clifford, Alessandro Rigolon

An under-appreciated reason why voters oppose dense new housing, especially in less-dense neighborhoods: they think it looks ugly and want to prevent that, even in other neighborhoods.

Some of what we think is NIMBYism might not be!

Reposted by Efrén O. Pérez, Valerie Mueller, Sylvain Laurens

aprecruit.berkeley.edu/JPF05187

youtube.com/watch?v=Ay4D...