How Medicine Works and When It Doesn't in bookstores now!

/🧵

/🧵

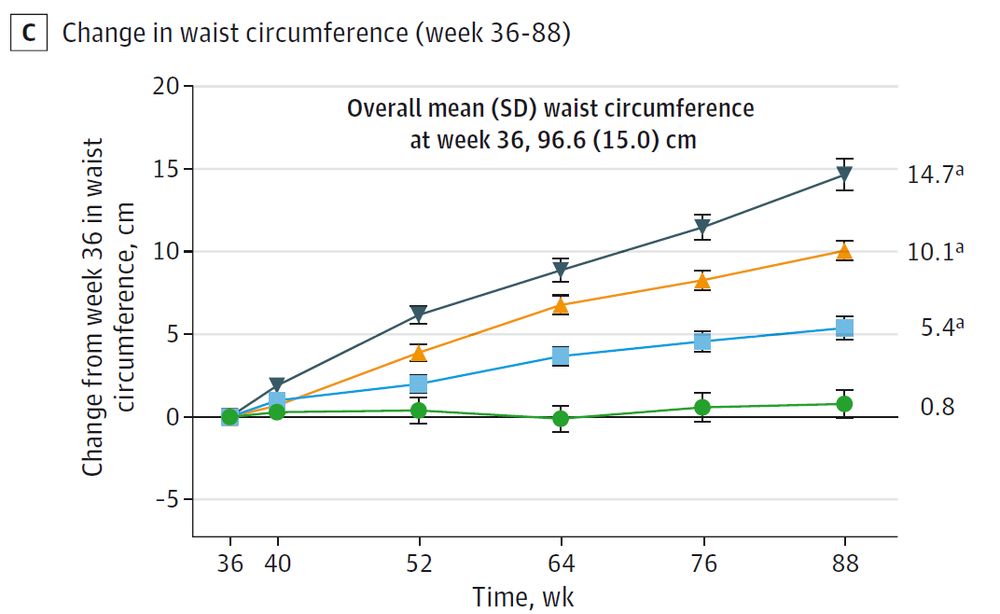

We are in a new paradigm of chronic weight management. "Miracle" implies a cure. This is a treatment. And right now, it looks like it might be a forever one.

We are in a new paradigm of chronic weight management. "Miracle" implies a cure. This is a treatment. And right now, it looks like it might be a forever one.

Was it age? BMI? Insulin levels?

Answer: None of them. Nothing at baseline predicted who would be able to keep the weight off. We are essentially flying blind.

Was it age? BMI? Insulin levels?

Answer: None of them. Nothing at baseline predicted who would be able to keep the weight off. We are essentially flying blind.

This data confirms they do NOT work that way. The thermostat is still set where it always was. Once the drug leaves your system, biology fights to get you back to your starting weight.

This data confirms they do NOT work that way. The thermostat is still set where it always was. Once the drug leaves your system, biology fights to get you back to your starting weight.

This waterfall plot is dramatic. Each bar is one person.

82.5% of people regained significant weight. Almost NO ONE could maintain the loss without the drug.

This waterfall plot is dramatic. Each bar is one person.

82.5% of people regained significant weight. Almost NO ONE could maintain the loss without the drug.

The setup: Participants took tirzepatide for 36 weeks. They lost ~20% of their body weight.

Then, half were switched to placebo. The other half stayed on the drug.

buff.ly/mCCtwHc

The setup: Participants took tirzepatide for 36 weeks. They lost ~20% of their body weight.

Then, half were switched to placebo. The other half stayed on the drug.

buff.ly/mCCtwHc

More here in my @medscape column this week: buff.ly/pM9bU3k

More here in my @medscape column this week: buff.ly/pM9bU3k

• These were already alcohol and marijuana users. No idea what happens in non-users.

• This was smoked cannabis only.

• Lab behavior ≠ real-world behavior.

Still, it lines up intriguingly with declining alcohol consumption since cannabis decriminalization.

• These were already alcohol and marijuana users. No idea what happens in non-users.

• This was smoked cannabis only.

• Lab behavior ≠ real-world behavior.

Still, it lines up intriguingly with declining alcohol consumption since cannabis decriminalization.

Average number of drinks:

• Placebo: ~3

• Low-dose THC: 2.4

• High-dose THC: 2.1

Nice dose-response. Statistically significant. And the direction is reversed from the authors’ original hypothesis.

Average number of drinks:

• Placebo: ~3

• Low-dose THC: 2.4

• High-dose THC: 2.1

Nice dose-response. Statistically significant. And the direction is reversed from the authors’ original hypothesis.

The reality: basically the exact opposite.

The reality: basically the exact opposite.

For two hours, participants could drink up to eight mini drinks. But for every drink they didn’t consume, they earned $3. A tidy little behavioral economics setup.

For two hours, participants could drink up to eight mini drinks. But for every drink they didn’t consume, they earned $3. A tidy little behavioral economics setup.

• a placebo joint

• a 3.1% THC joint

• a 7.2% THC joint

(in random order)

• a placebo joint

• a 3.1% THC joint

• a 7.2% THC joint

(in random order)

Complementarity: marijuana makes you more likely to drink; lower inhibitions, more risk-taking, maybe more craving.

Complementarity: marijuana makes you more likely to drink; lower inhibitions, more risk-taking, maybe more craving.