How Medicine Works and When It Doesn't in bookstores now!

/🧵

/🧵

Was it age? BMI? Insulin levels?

Answer: None of them. Nothing at baseline predicted who would be able to keep the weight off. We are essentially flying blind.

Was it age? BMI? Insulin levels?

Answer: None of them. Nothing at baseline predicted who would be able to keep the weight off. We are essentially flying blind.

This waterfall plot is dramatic. Each bar is one person.

82.5% of people regained significant weight. Almost NO ONE could maintain the loss without the drug.

This waterfall plot is dramatic. Each bar is one person.

82.5% of people regained significant weight. Almost NO ONE could maintain the loss without the drug.

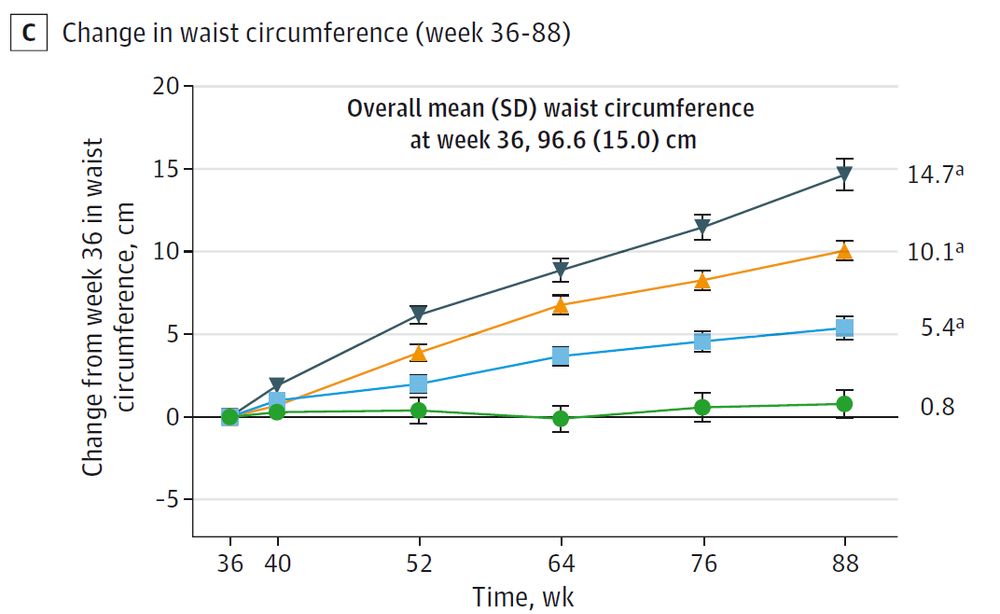

The setup: Participants took tirzepatide for 36 weeks. They lost ~20% of their body weight.

Then, half were switched to placebo. The other half stayed on the drug.

buff.ly/mCCtwHc

The setup: Participants took tirzepatide for 36 weeks. They lost ~20% of their body weight.

Then, half were switched to placebo. The other half stayed on the drug.

buff.ly/mCCtwHc

The miracle has a problem: It ends when the prescription runs out.

Let's look at the data on the "Rebound Effect." 🧵

The miracle has a problem: It ends when the prescription runs out.

Let's look at the data on the "Rebound Effect." 🧵

Average number of drinks:

• Placebo: ~3

• Low-dose THC: 2.4

• High-dose THC: 2.1

Nice dose-response. Statistically significant. And the direction is reversed from the authors’ original hypothesis.

Average number of drinks:

• Placebo: ~3

• Low-dose THC: 2.4

• High-dose THC: 2.1

Nice dose-response. Statistically significant. And the direction is reversed from the authors’ original hypothesis.

For two hours, participants could drink up to eight mini drinks. But for every drink they didn’t consume, they earned $3. A tidy little behavioral economics setup.

For two hours, participants could drink up to eight mini drinks. But for every drink they didn’t consume, they earned $3. A tidy little behavioral economics setup.

• a placebo joint

• a 3.1% THC joint

• a 7.2% THC joint

(in random order)

• a placebo joint

• a 3.1% THC joint

• a 7.2% THC joint

(in random order)

Complementarity: marijuana makes you more likely to drink; lower inhibitions, more risk-taking, maybe more craving.

Complementarity: marijuana makes you more likely to drink; lower inhibitions, more risk-taking, maybe more craving.

"They're sharing a drink they call loneliness, but it's better than drinking alone." - Billy Joel, 1973

Turns out he understood this paradox 50 years before the research caught up.

"They're sharing a drink they call loneliness, but it's better than drinking alone." - Billy Joel, 1973

Turns out he understood this paradox 50 years before the research caught up.

Most people in the study were in BOTH categories simultaneously.

Most people in the study were in BOTH categories simultaneously.

But the fascinating thing about this new PLOS One paper: loneliness and social connection aren't opposites.

buff.ly/xcNMxg1

But the fascinating thing about this new PLOS One paper: loneliness and social connection aren't opposites.

buff.ly/xcNMxg1

Some kids who wouldn't normally need psychiatric care get pushed over that edge by doxycycline. Now they're in the study group, but they're actually the HEALTHIEST kids in that group.

Some kids who wouldn't normally need psychiatric care get pushed over that edge by doxycycline. Now they're in the study group, but they're actually the HEALTHIEST kids in that group.

First, there's no clear dose-response effect. Higher doses should show stronger effects if this is causal. The medium dose looks best here, which is... odd.

First, there's no clear dose-response effect. Higher doses should show stronger effects if this is causal. The medium dose looks best here, which is... odd.