Thanks for reading!

🚨 It's PAPER* DAY! Which means #scicomm thread!

🧵⬇️🔭🪐🧪

*pre-print!

arxiv.org/abs/2508.18964

Thanks for reading!

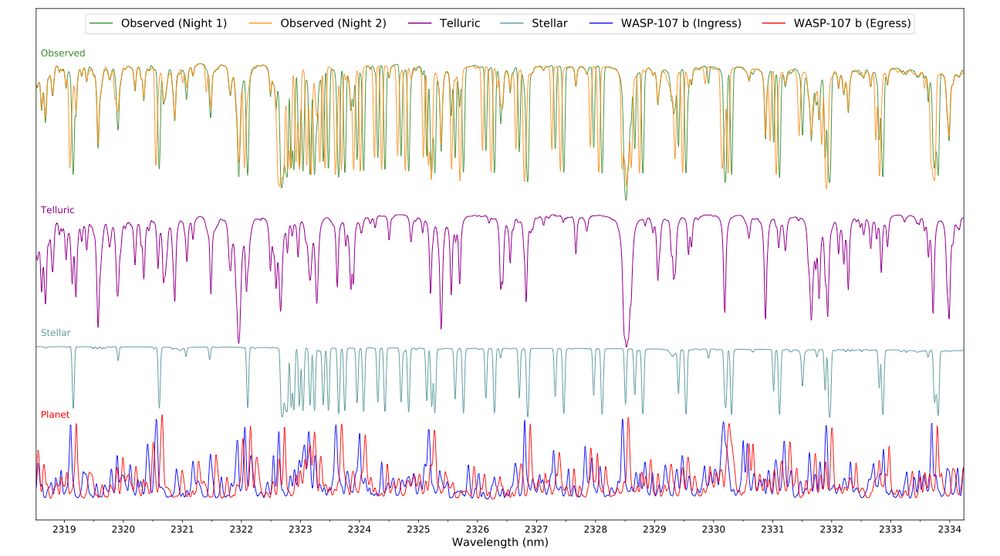

To do so, we take advantage of the 3x distinct and resolved Doppler shifts/frames I mentioned earlier—something only possible from the ground.

To do so, we take advantage of the 3x distinct and resolved Doppler shifts/frames I mentioned earlier—something only possible from the ground.

Space-based observations don't have tellurics ✅, but aren't high-res enough to resolve these Doppler shifts ❌.

Space-based observations don't have tellurics ✅, but aren't high-res enough to resolve these Doppler shifts ❌.

1) Lots of chemical info to exploit in the optical—of interest for 🪐 host chemistry.

2) Beware of naively trusting M/K dwarf physical model spectra—they aren't (currently) a good match to reality & this affects recovered stellar properties.

3) I've helpfully quantified some of this mismatch!

1) Lots of chemical info to exploit in the optical—of interest for 🪐 host chemistry.

2) Beware of naively trusting M/K dwarf physical model spectra—they aren't (currently) a good match to reality & this affects recovered stellar properties.

3) I've helpfully quantified some of this mismatch!