Ozikoro.com

Iron rod terminating at one end in brass image of a woman suckling a child, at the other in a brass serpent; the brass partially overlaid with copper.

Production date

1912-13

Location : Obo ( modern day Kwara state)

Photo credit: British museum

Iron rod terminating at one end in brass image of a woman suckling a child, at the other in a brass serpent; the brass partially overlaid with copper.

Production date

1912-13

Location : Obo ( modern day Kwara state)

Photo credit: British museum

Carved mask in form of young man. Light brown wood, painted black eyebrows, black painted hair in modern style. Eyes pierced. Suspension loop of string.

Made by: Anang (modern day Akwaibom state) in 1930.

Photo credit: British museum

Carved mask in form of young man. Light brown wood, painted black eyebrows, black painted hair in modern style. Eyes pierced. Suspension loop of string.

Made by: Anang (modern day Akwaibom state) in 1930.

Photo credit: British museum

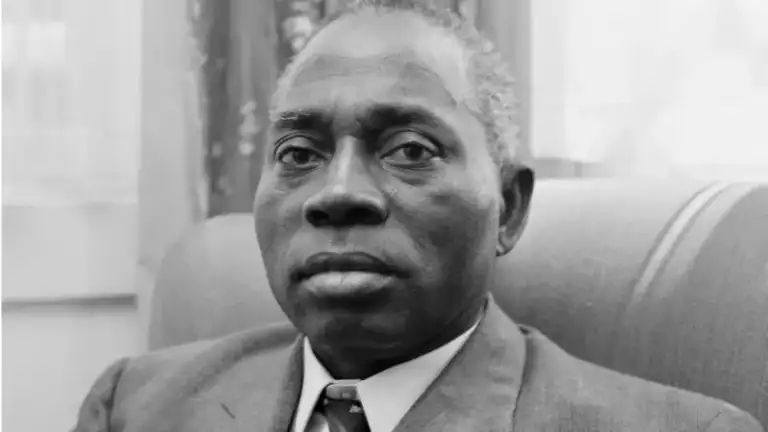

Chief Louis Nwachukwu Mbanefo remains one of the most distinguished legal minds in Nigerian history. Known as “the first Nigerian to be appointed a High Court Judge

Read more:

ozikoro.com/chief-louis-...

Chief Louis Nwachukwu Mbanefo remains one of the most distinguished legal minds in Nigerian history. Known as “the first Nigerian to be appointed a High Court Judge

Read more:

ozikoro.com/chief-louis-...

Garment Composed of seven broad strips hand sewn together. Weft-faced weave. Hand spun white cotton warp; white and indigo-dyed cotton weft bands. Hand sewn hems at both ends.

Made by: Ogori-Magongo (modern day kogi state) in 1950.

Photo credit: British museum

Garment Composed of seven broad strips hand sewn together. Weft-faced weave. Hand spun white cotton warp; white and indigo-dyed cotton weft bands. Hand sewn hems at both ends.

Made by: Ogori-Magongo (modern day kogi state) in 1950.

Photo credit: British museum

Textile made of two panels of grass cloth sewn together, woven with stripes of varying width coloured white, black, blue, red and yellow.

Made by: Ibibio in 1887 ( modern day Cross River state

Photo credit: British museum

Textile made of two panels of grass cloth sewn together, woven with stripes of varying width coloured white, black, blue, red and yellow.

Made by: Ibibio in 1887 ( modern day Cross River state

Photo credit: British museum

Frame 1:

Iron spear-head

Frame 2:

Composite spear with iron barbed head, metal ring and wooden shaft.

Production date

1905-14

Found most likely among the Ugep tribe in modern day Cross River state.

Photo credit: British museum

Frame 1:

Iron spear-head

Frame 2:

Composite spear with iron barbed head, metal ring and wooden shaft.

Production date

1905-14

Found most likely among the Ugep tribe in modern day Cross River state.

Photo credit: British museum

Musical instrument

Wooden sansa with cane keys.

Production date: 1905-14

Found/Acquired: ( most likely from the Efik tribe) Cross River State .

Photo credit: British museum

Musical instrument

Wooden sansa with cane keys.

Production date: 1905-14

Found/Acquired: ( most likely from the Efik tribe) Cross River State .

Photo credit: British museum

Sacrificial knife with an iron blade, and handle of wood and skin, with cotton stuffing.

Found and acquired most likely from the Ugep tribe in modern day Cross River state.

Year :1900

Photo credit: British museum

Sacrificial knife with an iron blade, and handle of wood and skin, with cotton stuffing.

Found and acquired most likely from the Ugep tribe in modern day Cross River state.

Year :1900

Photo credit: British museum

A large group of adult males standing in rows leading from river bank, "passing up yams". Forest on opposite bank. Snapshots taken in Southern Nigeria during The Aro Punitive Expedition 1901.

Ethnicity: Efik

Photo credit: the British museum

A large group of adult males standing in rows leading from river bank, "passing up yams". Forest on opposite bank. Snapshots taken in Southern Nigeria during The Aro Punitive Expedition 1901.

Ethnicity: Efik

Photo credit: the British museum

View of Cross River showing a settlement on the bank.

View of Cross River showing a settlement on the bank.

Southern Nigeria, view of Cross River. Shelters and small groups of adult males on near bank. Steam-boat "Jubilee" near far bank. Trees on far bank.

Taken in 1901

Photo credit: British museum

Southern Nigeria, view of Cross River. Shelters and small groups of adult males on near bank. Steam-boat "Jubilee" near far bank. Trees on far bank.

Taken in 1901

Photo credit: British museum

Wooden mask with mouth open showing metal teeth; headdress made of stuffed woven fabric and back of haad covered with the same; stands on a circular cane base.

Made by: Ekoi ( modern day Cross River state)

Production date: 1908

Photo credit: British museum

Wooden mask with mouth open showing metal teeth; headdress made of stuffed woven fabric and back of haad covered with the same; stands on a circular cane base.

Made by: Ekoi ( modern day Cross River state)

Production date: 1908

Photo credit: British museum

Iron hanging lamp with three-hinged hook and four spouts.

Production date: 1905-1914

Made by the Ekoi group ( modern day Cross River state)

Photo credit: British museum

Iron hanging lamp with three-hinged hook and four spouts.

Production date: 1905-1914

Made by the Ekoi group ( modern day Cross River state)

Photo credit: British museum

Snapshots taken in Southern Nigeria during The Aro Punitive Expedition 1901 showing :

Picture of adult males paddling a canoe on the Cross River.

Photo credit : British museum

Snapshots taken in Southern Nigeria during The Aro Punitive Expedition 1901 showing :

Picture of adult males paddling a canoe on the Cross River.

Photo credit : British museum

Bowl with hinged cover amde from calabashes, the cover ornamented with a trefoil pattern cut and burnt in; the hinge made of scarlet worsted cloth.

Made by: Ibibio (1887)

Modern day Cross River state

Photo credit: British museum

Bowl with hinged cover amde from calabashes, the cover ornamented with a trefoil pattern cut and burnt in; the hinge made of scarlet worsted cloth.

Made by: Ibibio (1887)

Modern day Cross River state

Photo credit: British museum

Circular bag with handle, made of glass beads sewn onto red-dyed cotton flannel. Turquoise and black beads on one side; black, yellow, red and blue beads on the other.

Production date: 1887

By: the Ibibio ethnicity ( Modern day Cross River state)

Circular bag with handle, made of glass beads sewn onto red-dyed cotton flannel. Turquoise and black beads on one side; black, yellow, red and blue beads on the other.

Production date: 1887

By: the Ibibio ethnicity ( Modern day Cross River state)

Cross-bow made of wood in two pieces; stock (a) and bow (b). Cord missing.

Made by : Edo ethnic group.

Found: 1875-1904 Northern Benin.( Modern day Edo State , Nigeria)

Photo credit: British museum

Cross-bow made of wood in two pieces; stock (a) and bow (b). Cord missing.

Made by : Edo ethnic group.

Found: 1875-1904 Northern Benin.( Modern day Edo State , Nigeria)

Photo credit: British museum

lost-wax cast in copper alloy. Vertical panels of decoration form openwork lattice; three panels with representations of human figures lie prone; hands tied behind backs; two birds (vultures?)

lost-wax cast in copper alloy. Vertical panels of decoration form openwork lattice; three panels with representations of human figures lie prone; hands tied behind backs; two birds (vultures?)

Archbishop Charles Heerey (1890-1967) , a man commonly credited with the formation of the Catholic women's organization amongst many other catholic organization in Nigeria.

photo credit: Archdiocese of Onitsha

Archbishop Charles Heerey (1890-1967) , a man commonly credited with the formation of the Catholic women's organization amongst many other catholic organization in Nigeria.

photo credit: Archdiocese of Onitsha

formed in remembrance of Bishop Shanahan, in 1949. Was central to education of the boy child in orlu division in the late colonial era and early post colonial era.

Located in Orlu, present day Imo state.

Photo credit : BSCORLU

formed in remembrance of Bishop Shanahan, in 1949. Was central to education of the boy child in orlu division in the late colonial era and early post colonial era.

Located in Orlu, present day Imo state.

Photo credit : BSCORLU

June 6, 1871 – December 25, 1943

Known as the apostle of Nigeria, Shanahan is credited for the spread of catholicism across southern igboland.

Photo credit: Spiritanroma

June 6, 1871 – December 25, 1943

Known as the apostle of Nigeria, Shanahan is credited for the spread of catholicism across southern igboland.

Photo credit: Spiritanroma

Bowl with round pedestal made of earthenware, with incised lines (a); with cover made of earthenware

Found:,Ebonyi State: Abakaliki

Year :1908

Photo credit: British museum

Bowl with round pedestal made of earthenware, with incised lines (a); with cover made of earthenware

Found:,Ebonyi State: Abakaliki

Year :1908

Photo credit: British museum

Ritual bowl made of pottery; shallow, with two squat figures on rim.

Found : Abakaliki( Modern day Ebonyi state)

Date:1978

Photo credit: British museum

Ritual bowl made of pottery; shallow, with two squat figures on rim.

Found : Abakaliki( Modern day Ebonyi state)

Date:1978

Photo credit: British museum

Made of iron; thin iron arrow-head with long, twisted handle.

Found/Acquired: Abakaliki - Modern day Ebonyi state (1900-1908)

Photo credit -British Museum.

Made of iron; thin iron arrow-head with long, twisted handle.

Found/Acquired: Abakaliki - Modern day Ebonyi state (1900-1908)

Photo credit -British Museum.

carved wood, seated male and female figures on a cylindrical pedestal, mounted on a basket work circlet and attached to it by a length of electric flex.

Made by: Ijaw in Delta state (discovered in the year 1954)

Photo credit: British museum

carved wood, seated male and female figures on a cylindrical pedestal, mounted on a basket work circlet and attached to it by a length of electric flex.

Made by: Ijaw in Delta state (discovered in the year 1954)

Photo credit: British museum