Isaac Lamb, MD

@isaaclamb01.bsky.social

12 followers

44 following

82 posts

PGY-4 neurology resident. Interested in clinical neurology, medical education, history, and nerd stuff.

Posts

Media

Videos

Starter Packs

Isaac Lamb, MD

@isaaclamb01.bsky.social

· Jul 12

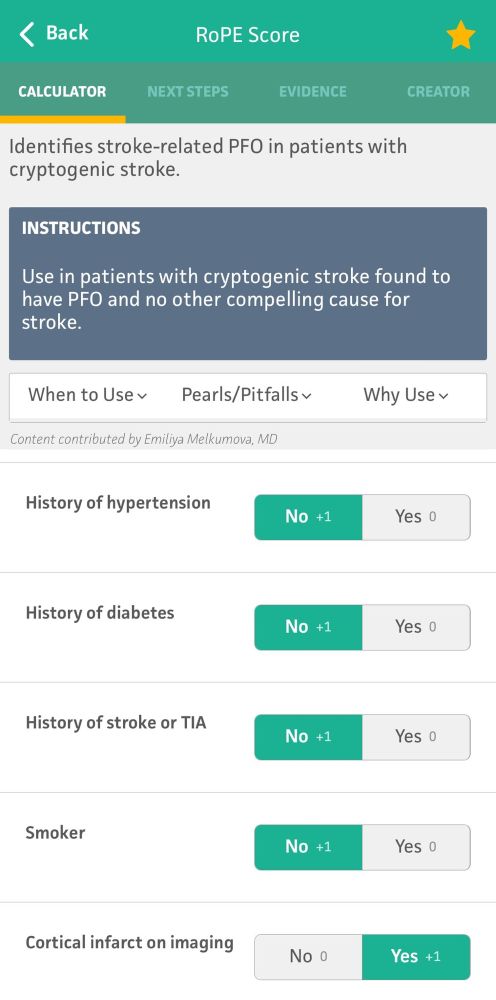

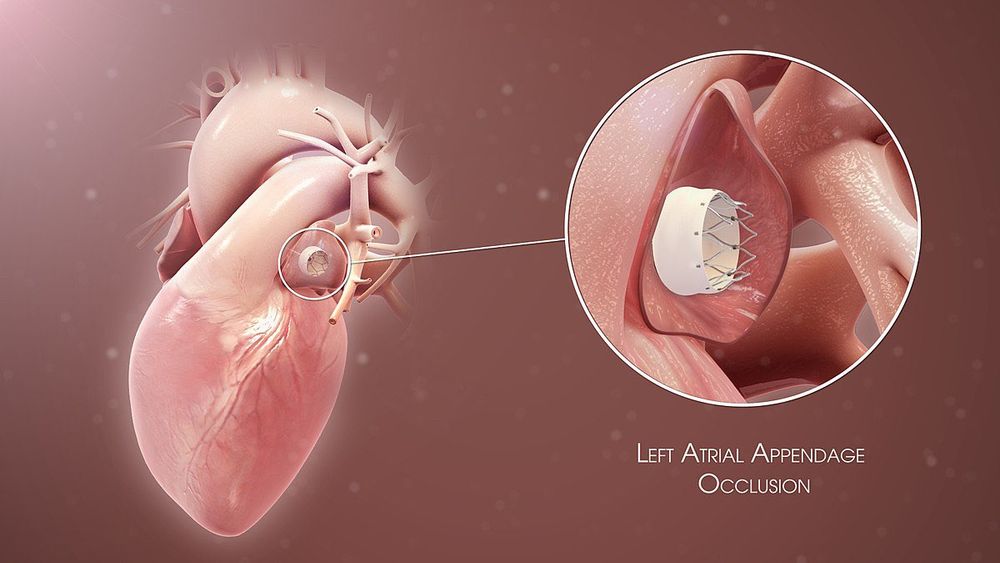

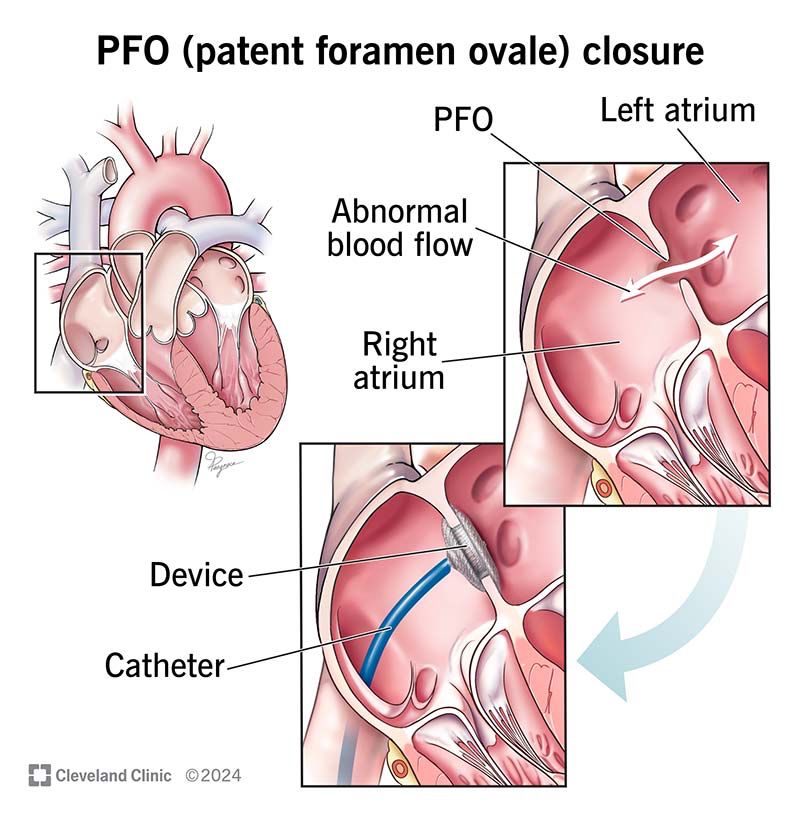

Patent Foramen Ovale: What It Is and How Serious It Can Be

Patent foramen ovale is a normal feature in your newborn’s heart. But when they still have it past age 3, it might need treatment. Learn more about this condition and its treatment.

my.clevelandclinic.org

Isaac Lamb, MD

@isaaclamb01.bsky.social

· Jul 12

Isaac Lamb, MD

@isaaclamb01.bsky.social

· Jul 12

Isaac Lamb, MD

@isaaclamb01.bsky.social

· Jul 12

Isaac Lamb, MD

@isaaclamb01.bsky.social

· Jul 12

Isaac Lamb, MD

@isaaclamb01.bsky.social

· Jul 12

Isaac Lamb, MD

@isaaclamb01.bsky.social

· Jul 12

Isaac Lamb, MD

@isaaclamb01.bsky.social

· Jul 12

Isaac Lamb, MD

@isaaclamb01.bsky.social

· Jul 12

Isaac Lamb, MD

@isaaclamb01.bsky.social

· Jul 12

Isaac Lamb, MD

@isaaclamb01.bsky.social

· Jul 12

Isaac Lamb, MD

@isaaclamb01.bsky.social

· Jul 12

Isaac Lamb, MD

@isaaclamb01.bsky.social

· Jul 12