https://carlsaganinstitute.cornell.edu/

Read the story of its first few days in space below!

🔭

Read the story of its first few days in space below!

🔭

🌌🎂

Stay tuned for posts this week that honor both his research legacy and his quest to make a more scientifically literate world…

🌌🎂

Stay tuned for posts this week that honor both his research legacy and his quest to make a more scientifically literate world…

We’ve found worlds orbiting all sorts of stars, from tiny, slow-burning reds to fast-living blue-whites to middle-of-the-road, prime-of-their-life yellows like our own...

We’ve found worlds orbiting all sorts of stars, from tiny, slow-burning reds to fast-living blue-whites to middle-of-the-road, prime-of-their-life yellows like our own...

alphacubesat.cornell.edu

alphacubesat.cornell.edu

Signs of alien life? Not yet...

Take a look for yourself at real data in the James Webb Space Telescope graph, and read more about it below! 🔭

Signs of alien life? Not yet...

Take a look for yourself at real data in the James Webb Space Telescope graph, and read more about it below! 🔭

Let's examine how Earth's reflected light over time can aid in the search for life!

Let's examine how Earth's reflected light over time can aid in the search for life!

This distinguished prize is awarded by the Division for Planetary Sciences (DPS) of the American Astronomical Society.

This distinguished prize is awarded by the Division for Planetary Sciences (DPS) of the American Astronomical Society.

Many Carl Sagan Institute researchers work with “spectra”—light we observe from other worlds, which we can split into a full spectrum of colors.

Many Carl Sagan Institute researchers work with “spectra”—light we observe from other worlds, which we can split into a full spectrum of colors.

🔭 Stay tuned!

🔭 Stay tuned!

The exposures were taken using the 102-year-old f/15 Irving P. Church 12" Refractor at the Fuertes Observatory, stacked in Siril and post-processed in Photoshop.

The exposures were taken using the 102-year-old f/15 Irving P. Church 12" Refractor at the Fuertes Observatory, stacked in Siril and post-processed in Photoshop.

This is 124 x 30-second frames, stacked in Siril.

This is 124 x 30-second frames, stacked in Siril.

This is 11 3-minute exposures, stacked, taken through the Irving P. Church 12-inch refractor at the Cornell University Fuertes Observatory.

This is 11 3-minute exposures, stacked, taken through the Irving P. Church 12-inch refractor at the Cornell University Fuertes Observatory.

Rubin has the largest digital camera in the world, and it's ready to revolutionize astronomy! Over the next decade, it will discover 2000x MORE galaxies than the 10 million shown below.

Let's explore how its images compare to other telescopes 🔭

Rubin has the largest digital camera in the world, and it's ready to revolutionize astronomy! Over the next decade, it will discover 2000x MORE galaxies than the 10 million shown below.

Let's explore how its images compare to other telescopes 🔭

Dr. MacDonald's team has re-analyzed earlier data, finding no evidence for life on K2-18 b: arxiv.org/abs/2501.18477

Read more below!

Dr. MacDonald's team has re-analyzed earlier data, finding no evidence for life on K2-18 b: arxiv.org/abs/2501.18477

Read more below!

An analysis of exoplanet K2-18 b points to the existence of dimethyl sulfide, a molecule produced by photosynthesizing plankton on Earth—but proving that this sign is real, and that life is the only explanation, is a difficult task.

arxiv.org/abs/2504.12267

An analysis of exoplanet K2-18 b points to the existence of dimethyl sulfide, a molecule produced by photosynthesizing plankton on Earth—but proving that this sign is real, and that life is the only explanation, is a difficult task.

arxiv.org/abs/2504.12267

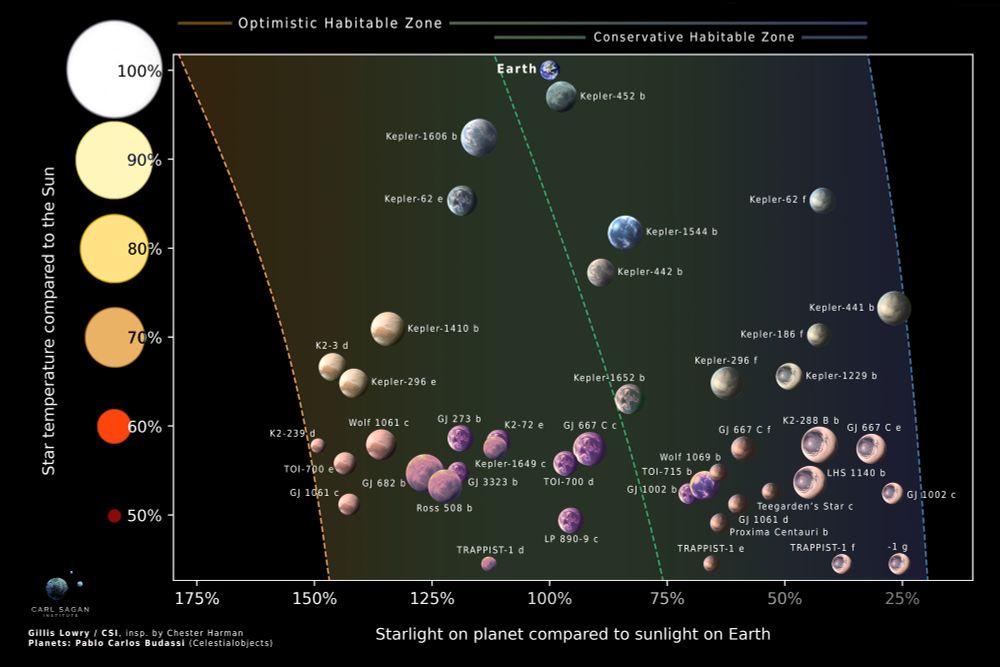

A recently-submitted CSI paper puts new "habitable zone" planets on the map, which may be the right temperature for liquid water on their surfaces. Signs of life might also be chemically detectable in their atmospheres.

🔭

A recently-submitted CSI paper puts new "habitable zone" planets on the map, which may be the right temperature for liquid water on their surfaces. Signs of life might also be chemically detectable in their atmospheres.

🔭

www.ithacajournal.com/story/news/2...

Image 2: CAS Vice President Andrew Lewis with the 102-year-old telescope

🔭

www.ithacajournal.com/story/news/2...

Image 2: CAS Vice President Andrew Lewis with the 102-year-old telescope

🔭

"Worm" just refers to a full Moon in March. This particular full moon is also a lunar eclipse, where the Moon passes into Earth's shadow. Light bending through our atmosphere causes a blood-red color!

"Worm" just refers to a full Moon in March. This particular full moon is also a lunar eclipse, where the Moon passes into Earth's shadow. Light bending through our atmosphere causes a blood-red color!

🔭

🔭

TODAY at 2 EST, tune into the Cornell Symphony Orchestra's cosmic concert! 🔭

Livestream: vod.video.cornell.edu/media/mediai...

TODAY at 2 EST, tune into the Cornell Symphony Orchestra's cosmic concert! 🔭

Livestream: vod.video.cornell.edu/media/mediai...

The lecture will be in Appel Commons Room 303 on Cornell's north campus, or on Zoom as linked on our website at www.cornellastrosociety.org/lecture-series.

The lecture will be in Appel Commons Room 303 on Cornell's north campus, or on Zoom as linked on our website at www.cornellastrosociety.org/lecture-series.

In-person coffee hour tomorrow, and an astronomical orchestra concert on Sunday in-person or online!

Concert livestream: tinyurl.com/2tp5ry35

More: carlsaganinstitute.cornell.edu/news/concert-celebrates-wonders-space-march-2

In-person coffee hour tomorrow, and an astronomical orchestra concert on Sunday in-person or online!

Concert livestream: tinyurl.com/2tp5ry35

More: carlsaganinstitute.cornell.edu/news/concert-celebrates-wonders-space-march-2