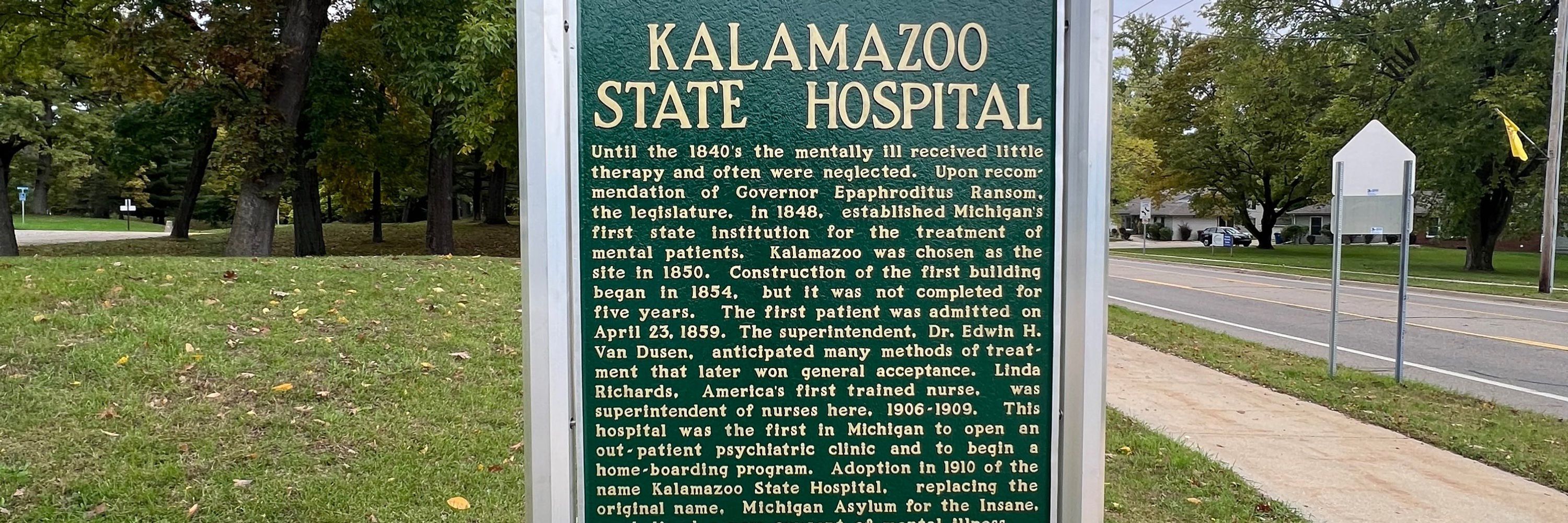

Historical Marker Ahead

@historicalmarker.bsky.social

2.1K followers

1.5K following

3.6K posts

Yes, I’m pulling the car over to look at plaques. I’ll be just a minute. Not a historian, but did minor in history at Indiana University. Formerly notgoingpro on other socials.

Posts

Media

Videos

Starter Packs

Reposted by Historical Marker Ahead

Reposted by Historical Marker Ahead

Reposted by Historical Marker Ahead

Reposted by Historical Marker Ahead

Reposted by Historical Marker Ahead

Reposted by Historical Marker Ahead

Reposted by Historical Marker Ahead

Reposted by Historical Marker Ahead

Reposted by Historical Marker Ahead

![Marker at the Sand Creek Massacre Historic Site in the plains of Eastern Colorado. It reads:

On November 29, 1864, U.S. Colonel John Chivington and 700 volunteer troops attacked an encampment of Cheyenne and Arapaho along Sand Creek. [My note: they had been forced into that area and were in US eyes legally there, but Chivington attacked anyway, even though there were surrender and U.S. flags on the tipis.] The thunderous approach of horses galloping toward camp at dawn sent hundreds fleeing from their tipis. Many were shot and killed as they ran. While warriors fought back, escapees frantically dug pits to hide in along the banks of Sand Creek - cannonballs later bombarded them.

In the bloody aftermath, some of the soldiers mutilated dead bodies and looted the camp. Later, most of the village and its contents were burned or destroyed.

Among the slain were chiefs War Bonnet, White Antelope, Lone Bear, Yellow Wolf, Big Man, Bear Man, Spotted Crow, Bear Robe, and Left Hand - some who had worked diligently to negotiate peace.

Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site commemorates all who perished and survived this horrific event, Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Colorado soldiers. This site also symbolizes the struggle of Native Americans to maintain their way of life on traditional lands.

(Photo Caption)

Cheyenne Chief War Bonnet, pictured during a visit to President](https://cdn.bsky.app/img/feed_thumbnail/plain/did:plc:bgncrecbivzjcgqzln3gzw67/bafkreih7pxiqpr4kv7eipm3kbossmt7u6m5notgzyxhosq5en4qndkmptu@jpeg)