Marijn van Putten

@phdnix.bsky.social

1.8K followers

150 following

690 posts

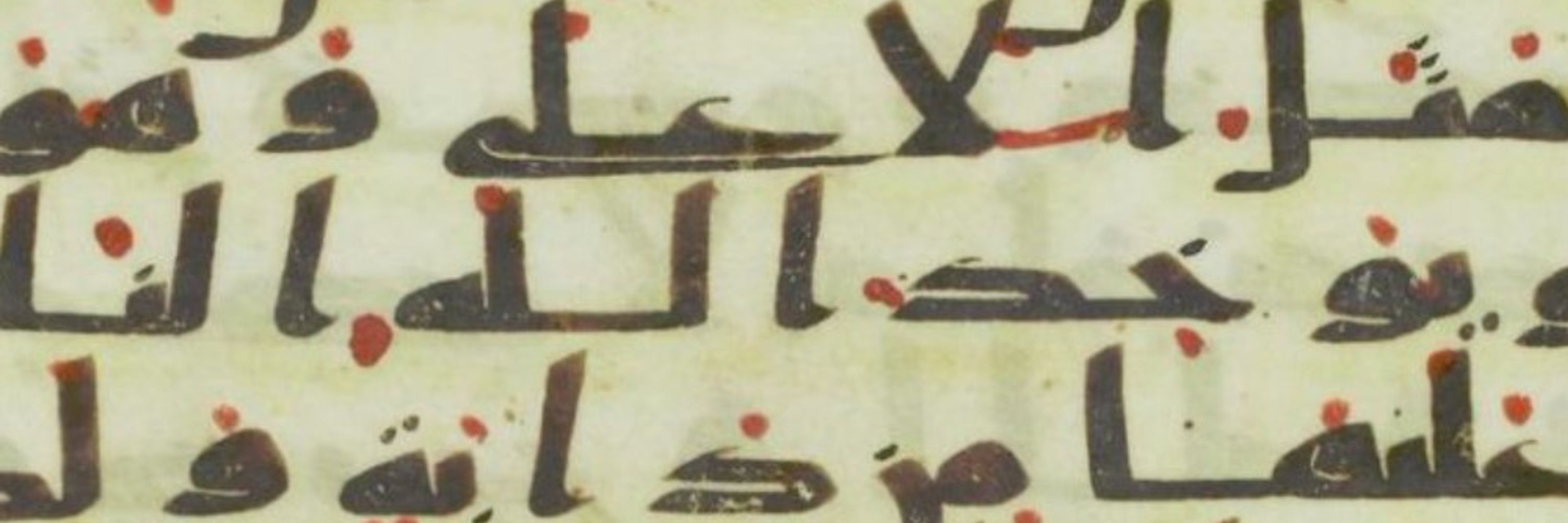

Historical Linguist; Working on Quranic Arabic and the linguistic history of Arabic and Tamazight. Game designer for Team18k

Posts

Media

Videos

Starter Packs