Mike Mazur

@mikemazur.bsky.social

23 followers

30 following

10 posts

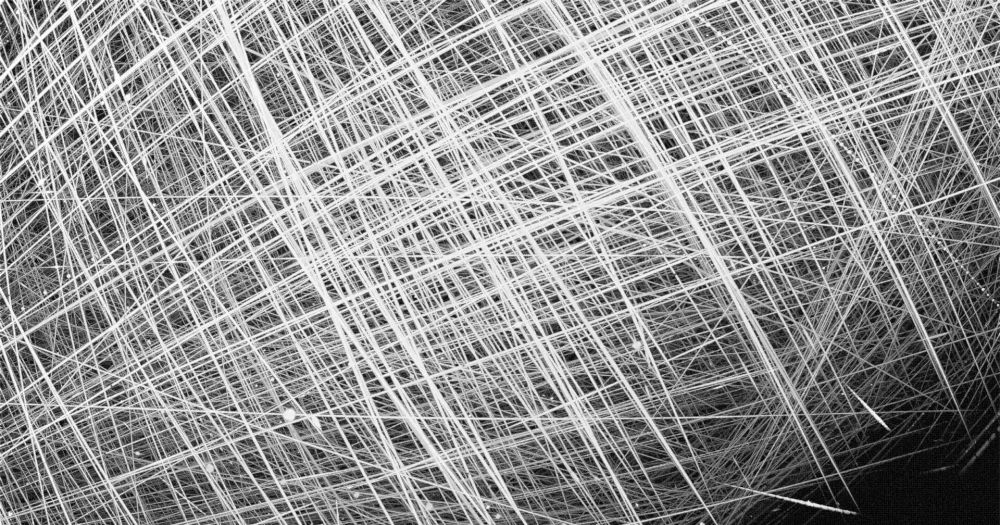

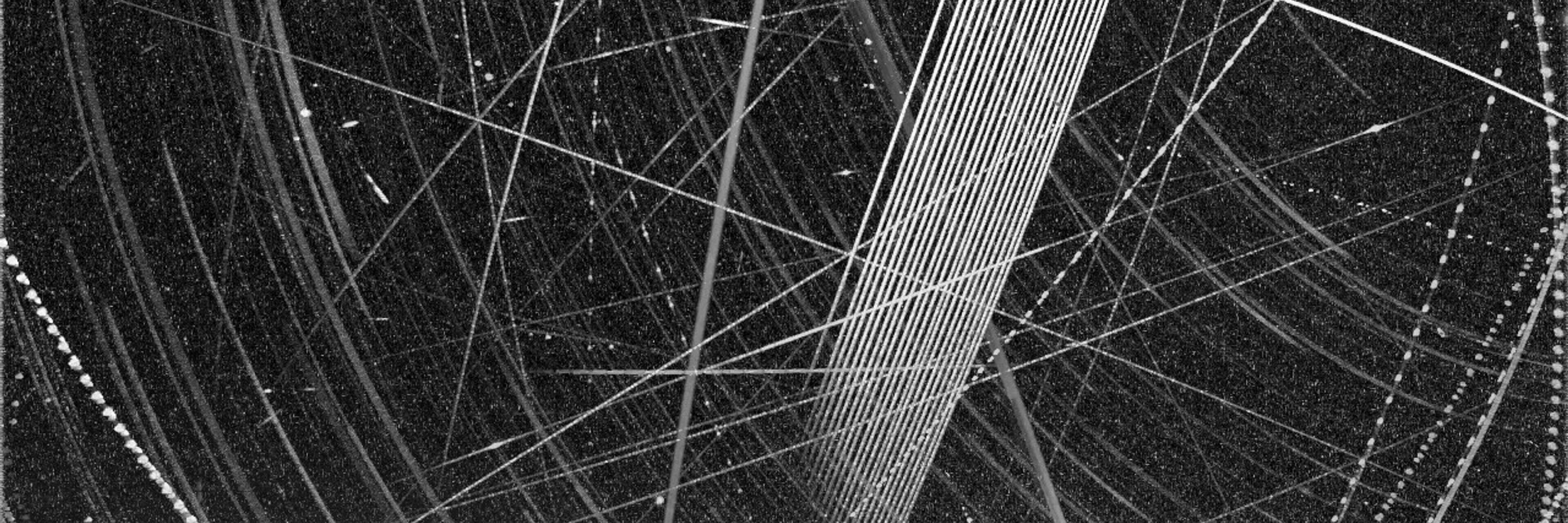

Meteors, satellites, and other fun stuff :-)

Posts

Media

Videos

Starter Packs

Mike Mazur

@mikemazur.bsky.social

· Jun 3

Mike Mazur

@mikemazur.bsky.social

· Jun 3

Mike Mazur

@mikemazur.bsky.social

· Jun 3

Reposted by Mike Mazur